Organics, Carbon Farming, and Cultivating Soil (and Values!)

/Last weekend I was at the Northeast Organic Farming Association of NY’s annual winter conference. For those of you following along, I think my workshop went well (if you are interested in learning more about that, check out last week’s blog!). Besides attending some great workshops and meeting new folks at the CSA fair, this weekend got me energized about the season but also a bit mentally overwhelmed thinking about what to share from the weekend.

One thing I realized that we don’t really talk about much, both as individual farmers and as part of the larger farming community, is why we grow organically. To us, growing up with families gardening or homesteading, organic is just agriculture as we’ve always done it. [Okay, confession time: when I was a kid with horses growing up in Indiana, there were these gross flies that would lay eggs on their legs, and we were taught by the trainer to spray Raid—like nasty, toxic household Raid--on the horses to kill the flies. A) so not organic, B) so incredibly disgusting in hindsight, and C) I also totally sprayed Raid on my clothes as well to keep the flies off which can’t be good for a kid!]

Aside from some childhood digressions, we are both just really used to farming how we do, so it struck me at the conference to learn that there are only 25,000 certified organic producers nationwide, with NY hosting the third largest number of certified farms—1108 farms with over $5000 in sales. 59 of these are in Madison County, which means Hartwood Farm is 1.7% of organic farms in our county. Those numbers don’t count all the other farms that aren’t certified organic but doing the good work of integrating greater sustainability into their operations, like using reduced tillage or intensive grazing or cover crops to improve soil health, all practices which also help soil better hold carbon out of the atmosphere.

This winter we’ve been watching the news from Australia’s fires in shock. Australia has the world’s most rapidly expanding organic or sustainably managed farm base, but all those farmers taking care of their ground can’t withstand the fires and the bigger planetary picture of rising temperatures.

This tragedy has been making us ask ourselves the hard questions about how our tiny piece of land and how we care for it has a place in the bigger global picture. Some days on the farm, it feels like we are doing a silly little thing, working so hard on our patch of ground and not making a dent in the bigger structural changes we want to be a part of. We race around all winter getting ready and then all spring planting, all summer harvesting, all fall cleaning up, cramming these tasks amid all the computer and outreach work, the deliveries and farmers markets and all the hundred tiny farm emergencies and dramas that pop up each day. There isn’t always the time for introspection or thinking or feeling connected to anything bigger.

And then other days we stop and realize that we are in this small group of people (farmers), and then an even smaller group within that (organic farmers) where we do have the power to make changes on the land.

What we strive for on our farm is to grow healthy and delicious produce for our members and customers, and get it to you all with help on how to use and enjoy it. We hope that this shared enjoyment of tasty meals can help build community and let families and folks have a space of simple relaxation, of chopping and heating and eating, where we don’t feel all the stress and anxiety that might be out there around us. (Sorry if this post is making you feel some of that stress, lol!)

And we want to do it in a way that leaves our farm, air, and water better off than when we started. As farmers, we are super nervous about the environment and about climate change, and about how challenges to production might impact the health and quality of our food and our land, and this is the area where we worry about doing enough. Is it “enough” to focus on feeding a few hundred families, or should we be doing something more? Does our work even make any impact in the bigger picture?

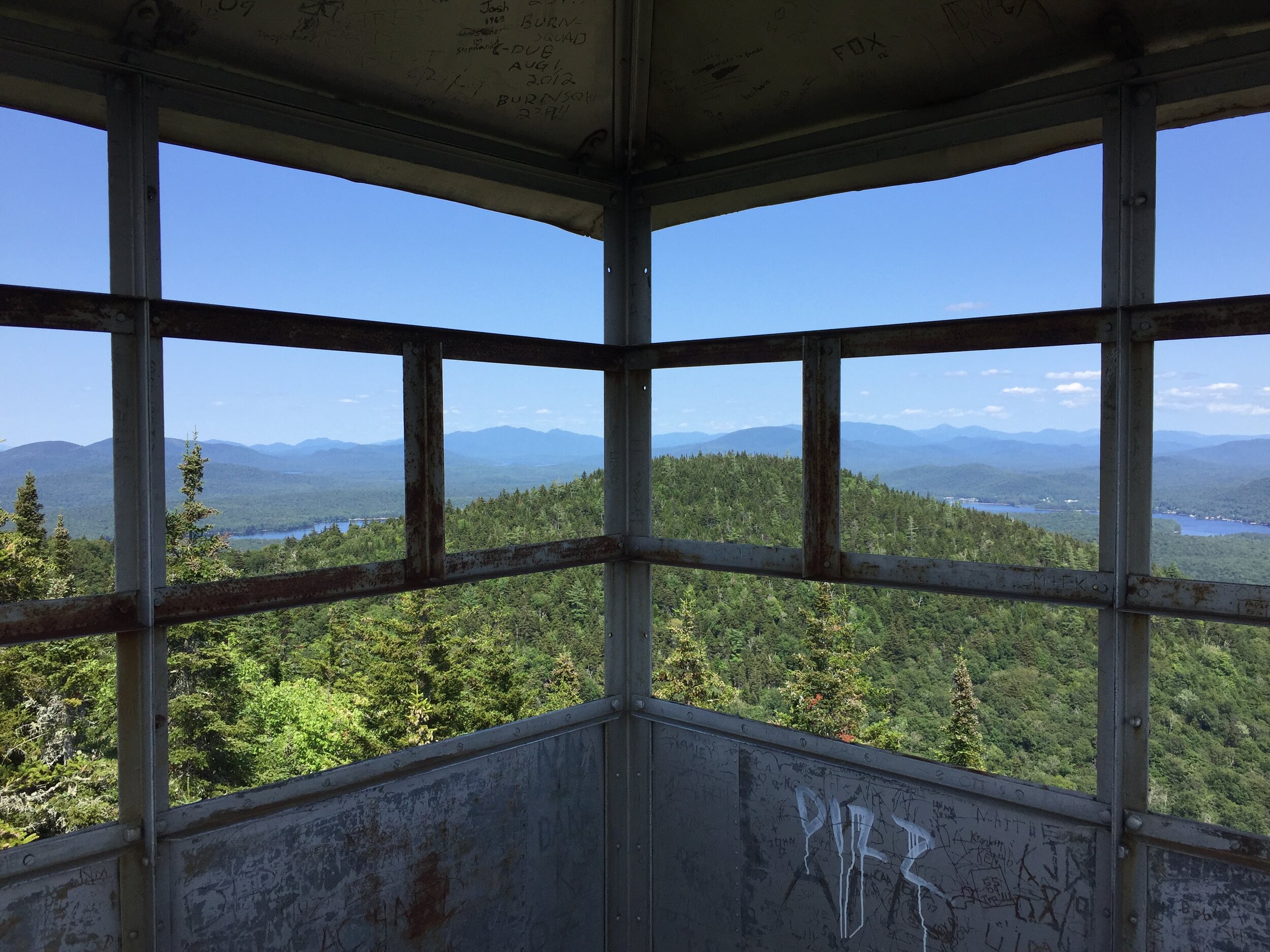

What’s really been interesting us recently is “carbon farming” or “regenerative farming,” two new phrases that are getting tossed around a lot to describe ways of land management that are quite well established in the sustainable ag community, but just now catching buzz more widely. The idea is that you can both not cause climate change by farming, as well as contribute to reducing climate change impact by increasing your land’s capacity to hold more carbon in its soil.

How carbon farming fits into a small farm like ours is by building up our soil organic matter percentage. More soil organic matter can hold on to more carbon in the soil, which keeps it out of the air. We can also increase vegetative cover on our ground—a covered ground releases less carbon into the air. There are still a lot of questions that science is working out—like how exactly the whole process works and what sort of impact different soil microbes have, but there does seem to be potential in carbon farming for helping mitigate climate change.

On our farm, we’ve implemented these practices largely over five years by building up enough crop fields that each season, half of our production areas are not used and planted to long season cover crops. These covers help us break up weed and disease cycles, while increasing the soil organic matter and carbon trapping capacity. Last year (2019) was the first year we started using fields that had so much time out of production, and it was amazing how much more fertility those areas had. This year we are continuing on this work, while moving on to the next phase of trying to source more organic plant mulches to further cover the soil and help boost carbon capture.

Carbon farming is definitely a win-win situation, but for the challenge of doing it (if it were cheap or easy, everyone would already be all in on it!). While all the practices help improve our soil and crops in quantity and quality, they also take a lot more time and money to manage, and they aren’t a quick fix (it literally took five years to see the first results). In a lot of ways, carbon farming is like organic farming—the end result is good for a lot of people and agro-ecological systems, but our societal’s economic system isn’t really structured to reward this slow path.

I’m a dork and like to relax by doing back of the napkin calculations, trying to cost out things like our farm’s impact on community food supply, or how many calories we grow out relative to calories inputted to run our farm, or the exact weight of plastic we use in our production per person we serve (check back in the next month for this followup, since I know a lot of folks out there are wondering the same!). The answers on these three are: a lot of people if you count based on value or nutrition over calories; about even since except for potatoes, veggies are so low calorie; and on the plastic, both more than I want but way less than I thought!

What frustrates me on the back of these napkins and in the rhetoric from the world around us is that we measure efficiency and economic viability against standards that don’t take into account the environment or communities or all sorts of other external and internal values. Even putting aside organics, a farmer with a thousand acres running a grass-fed regenerative beef operation on paper might appear less efficient next to a thousand acre farm growing corn. The beef farm needs more people to manage things, gets less calories an acre, and has to deal with the costly and expensive hassle of a long processing chain, while the corn producer has a more efficient system set up to handle their product, right up to commodity subsidies.

Yet there are all sorts of intangibles—from locking up carbon in the pastures to building up soil through intensive grazing, that don’t show up in the our current system’s accounting of the two operations. It costs a bit more to do things “right” by the environment, and our country has historically measured value, efficiency, and productivity by terms that don’t put much weight on environmental or climatic quality. When we build soil or trap carbon as small farmers, a lot of these costs are almost considered worthless in economic terms (except for their crop yield increases).

Getting a weekend away, meeting new and old farmer friends, and getting inspired to kick off a new growing season really has helped me feel re-energized to keep doing what we are doing to build soil and trap carbon, all while producing delicious veggies.

I don’t think we are alone as a farm, a local business, or a household in these decisions. How do you find the balance between values and efficiency? And what do you value most in your food or farms? We’d love to hear your way of thinking about the question!

Now I’m off to plan out our cover cropping strategy for 2020, and pick out the last of our seeds. Thanks so much for reading, and stay warm out there!